This blog describes my project to OCR the Gesta Porsennae (1458/1460) by Leonardo Dati (1408-1472) with OCR4all from high quality scans offered online by the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, of the ms. Vrb. lat. 411, a beautiful late fifteenth century manuscript from the library of Federico da Montefeltro.

OCR of manuscripts is in many ways the holy grail of OCR of historical media. On the one hand there are manuscripts with a script that is tantalizingly clean, on the other hand success has been limited, with high error rates. Software that is specifically geared towards manuscripts, has been rare so far. The only software specifically aiming at OCR of handwriting I know of is Transcribus (see the comments by Reul et al. 2019). With a stated lower limit of ground truth production of a hundred images this aims at projects with a substantial number of collaborators and/or long time perspective. This blogger, a single researcher always in a hurry, has neither. A rather successful attempt at ms-OCR was described by Jean-Baptiste Camps on the Graal-blog, using OCRopy (which is in the same family of software as OCR4all/Calamari). An in-depth discussion of the topic was recently given by Hawk 2019.

With twenty folia Dati’s text is relatively short (the text by design breaks off in the middle of a sentence; Dati claims that the “original”, from which he “translated”, had been damaged at that point). This will allow for a thorough correction of the text produced by OCR4all, but limits the production of ground truth (transcribing a large section of the text as GT would obviously defeat the purpose of OCR).

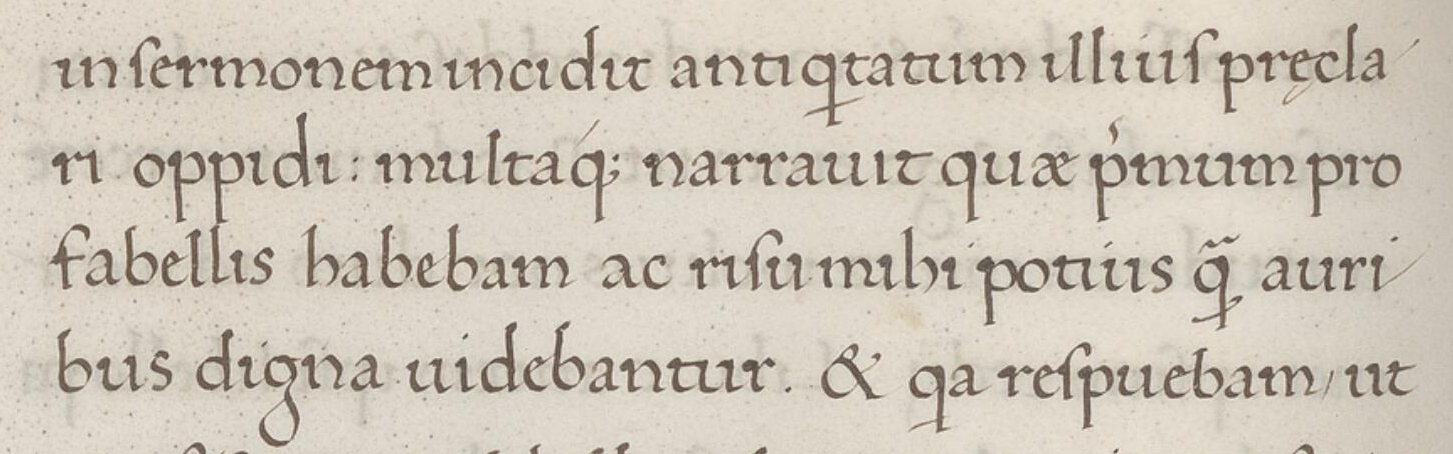

GT is for these reasons confined to seven pages (which is a ridiculously small amount), and the five font models produced have in the end between 90.7 and 96.9% accuracy, which is significantly worse than training for early printed books. The ms. exhibits several characteristics that make OCR difficult, such as letters flowing into each other (handwriting!), largely indistinguishable ‘ui/iu’, a flowery ‘g’ the lowest part of which is often cut off by segmentation, and the filling of lines with nonce characters to create a perfectly aligned right margin.

from BAV Vrb. lat 411 fol. 67v

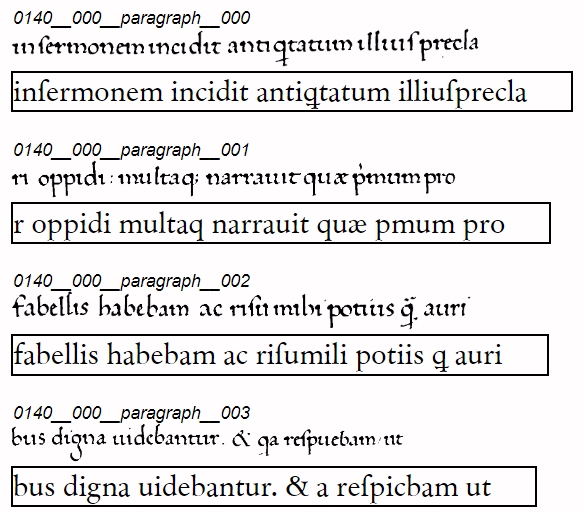

The result, after two rounds of training, is as follows:

OCR from BAV Vrb. lat 411 fol. 67v

Some types of mistakes are the same as in early printed books; especially the majuscules are for lack of training just as problematic as they are usually in print. The ‘x’ is not very well recognized, nor is majuscule ‘E’ which resembles ‘e’ magnified. Abbreviations are hardly ever recognized, since the parts of the graph are usually spread out and not contiguous. Some problems (such as the graphs for ‘que’ or ‘ct’) could have been solved with more training.

All in all I am quite content with the result. It needed a substantial amount of post-processing. This, however, was still considerably faster than typing a machine-readable text.

Literature

B.W. Hawk, “Modelling Medieval Hands: Practical OCR for Caroline Minuscule”, dhq 13,1 (2019). www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/13/1/000412/000412.html

Ch. Reul et al., OCR4all - An Open-Source Tool Providing a (Semi-)Automatic OCR Workflow for Historical Printings, applsci (2019). arxiv.org/pdf/1909.04032.pdf

Software and internet sites mentioned in this blog post: BAV Vrb. lat. 411, digi.vatlib.it/view/MSS_Urb.lat.411, Camps, Graal, graal.hypotheses.org/786, Transkribus, transkribus.eu/Transkribus/, OCR4all, github.com/OCR4all, EML-txt2txt, jramminger.github.io/emltxt2txt/.